You are here

Home ›Family of Waterville native Cletus Unterberger shares his WWII POW experience

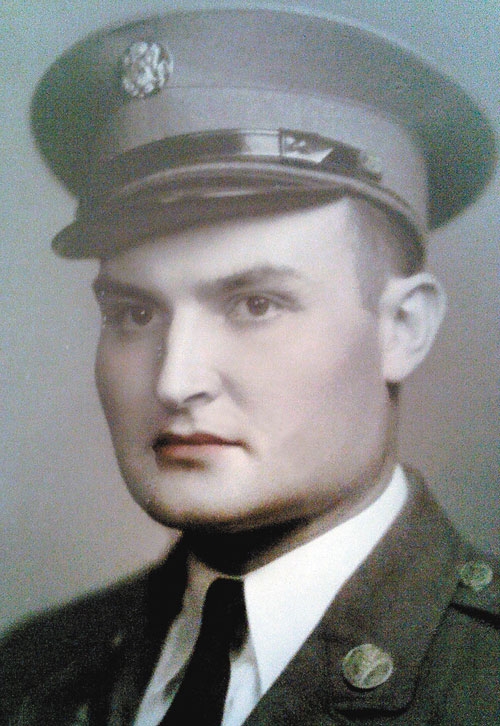

Cletus Unterberger

by Lissa Blake

Like many prisoners of war, Private First Class Medic Cletus Unterberger, never talked much about his time in captivity during World War II.

The son of John and Elizabeth Unterberger of Waterville, “Clete” served in the 168th infantry 34th (Red Bull) Division, which had the distinction of being the first U.S. division deployed to Europe during the war.

He was captured by the Germans February 17, 1943 during the Invasion of North Africa, just nine days after arriving on the front. He spent more than two years as a German prisoner of war, during which time he kept a secret diary of his life.

TELLING HIS STORY

A couple of years ago, Clete’s niece, Mary Lynn (Wagner) ReVoir, a 1978 graduate of Kee High School in Lansing, was honored when her Aunt Bernadette, Clete’s wife, asked for help in preserving his legacy. “I really didn’t know my uncle. He passed away in 1982,” said ReVoir. “Bernadette and Clete never had children, so she approached me and showed me some of his things from the war. There was a medic bag and his uniform, but most importantly his little diary he kept as a POW.”

ReVoir and Bernadette quickly went to work chronicling the story of her uncle’s service.

CLETE’S MILITARY CAREER

Cletus Unterberger was drafted and inducted into the U.S. Army May 29, 1941. He attended basic training at Jefferson Barracks, MO before receiving more specialized training as a medic.

At the end of April 1942, he left New York on the S.S. Santa Rosa headed for Larne, Ireland, where he stayed for 2-1/2 months before leaving for Scotland. He sailed on the S.S. Brazil to Lugton, Scotland before traveling to Liverpool, England and boarding the S.S. Otrando, which was headed to North Africa.

November 8, 1942, he arrived in North Africa. After less than three months, his unit left El B’iar and arrived on the front, February 8, 1943.

Nine days later, his unit was captured at Faid Pass, Sidi Bousid and arrived at Sfax February 18. Because he was a medic, he did not carry a gun.

In his well-preserved diary, Clete wrote, “Walked 110K (kilometers),” which is equal to approximately 68 miles. His diary recounts that February 22 he was at Sousse, and arrived in Tunis February 23, leaving for Naples March 3.

March 13 he left Naples and arrived in Mossberg, Germany via Brenner Pass March 16, where he stayed until March 27, when he was moved to Stalag IIIB, which was located on the Odor Canal near Furstenberg, Germany, about 30K (18.5 miles) from Berlin. In all, he spent time in four different prisoner-of-war camps.

FEW STORIES

Bernadette said she remembers Clete telling her a couple of things about his capture: the first was that a Ham (amateur) radio operator had called his parents back in Waterville to tell them the Germans had captured Clete’s group. The second was that when one of the German soldiers was emptying the Americans’ guns (following their capture), he shot himself in the foot.

“I said to Clete, ‘You didn’t laugh.’ He said, ‘If we’d have laughed, we would have been shot,’” remembered Bernadette.

RECORDING HISTORY

Other than that, Bernadette said Clete rarely talked about the place where he stayed in captivity for the next nine months. “He didn’t say much, but sometimes he would share some things. Like the soup they fed him was stringy… I never fixed sauerkraut, because he’d had his fill of it,” said Bernadette.

Clete hid his diary and a tiny pencil, which he used to record his life in captivity. He wrote that April 11, 1943, the men received their first boxes from the Red Cross and by July 21, they started arriving regularly.

His diary chronicles when he received each Red Cross parcel, which country it came from and what portion of the box he received, i.e. 1/2 or 1/4, as there weren’t enough to go around and sharing was par for the course.

He also recorded the number of times he helped the Germans with the injured, recording “German pay” owed to him, which he never saw.

Bernadette recounted a story Clete told about receiving one Red Cross box that contained some potatoes and butter. “Two men shared a box and they were excited they were going to have these potatoes. Someone nearby was cutting somebody’s hair and the wind came along and blew some hair and some of it got in their potatoes,” said Bernadette. “I asked him if he ate it anyway and he said, ‘Oh sure. Hair doesn’t have any taste.’ They were so hungry. I know they fought hunger and cold."

Clete’s diary chronicles being deloused and searched, living in a snake pit and fighting cold, hunger and smoke, among other things. Finally, April 29, 1945, Clete wrote, “April 29. Battle at Mooseburg. LIBERATION.”

COMING HOME

Diary entries after his release indicate he arrived at South Hampton, England and made several entries about the food he had obviously missed while being held prisoner. In South Hampton, he wrote, “Ate first apple and orange. GOOD FOOD.”

He arrived in Staten Island, NY June 3, 1945 where he recorded, “Had first Coke and hamburger.” At Camp Kilmer, June 3-5, he wrote “ate ice cream.”

Eventually, by the beginning of September, he made it by train as far as Marquette and hitched a ride on Highway 76 and got dropped off at the Sixteen School Road in rural Waterville.

In his memoir, ReVoir recounts, “Walking a mile to his parents’ farm, he quietly announced his arrival at the doorstep of the family farmhouse, with his mother and sisters in the kitchen. Together, they walked out to the field, greeting his father and brother. None of his family was aware of his pending return home.”

AFTER THE WAR

Clete and Bernadette met in 1953, when Clete was visiting his sister, Raphaela Huffman, in New Hampton. “I remember she called me to come over because they needed a fourth for cards,” said Bernadette. “We went together for a couple of years and married October 19, 1957."

Bernadette said in all the years they were together, she only really remembers Clete opening up about the war years on one occasion.

“We weren’t even married yet and we had gone with some friends to the circus in Waterloo. When we got back, I went over to get my car, he sat there and we visited and we just started to talk. That was really the only time he ever talked about it,” she said. “He never really talked about it to me, not to anybody. Maybe that was his way of trying to forget.”

She did say once in a while something would happen that would remind him of something unpleasant, such as fireworks on the Fourth of July. “Just the sound of the fireworks going off bothered him. We only went to see them once,” she said.

THE LATER YEARS

After their marriage, the Unterbergers took over Clete’s family farm, where they raised dairy and beef cattle and some hogs. Bernadette said she and her husband enjoyed a life of hard work together and spent most of their years tending to the farm.

“We didn’t travel much. We just worked … with all that, and there were just two of us, when we got through at night, we were tired,” she said.

The couple did, however, manage to make it to the Prisoner of War (POW) convention each year, where Clete would reminisce with friends with whom he was captured. He had several Army friends he stayed in touch with until his death in 1982 of a heart attack.

PRESERVING HIS STORY

Today, Bernadette, 91, lives in an assisted living facility in Shell Rock. She and ReVoir are still in search of a permanent home for Clete’s uniform or medic bag and any interested historical or veterans’ group is encouraged to email ReVoir at mlrevoir2@gmail.com for more information.

To view the complete Cletus Unterberger memoir compiled by Bernadette and her niece, visit http://iagenweb.org/wwii/WWIISurnamesU_V/UnterbergerCletusJ.html.

“This testimony demonstrates his perseverance to record only important dates and events without noting any personal fear, horror of war battles, not struggles of the life of a POW,” concludes ReVoir in the memoir.